The Washington Post, 1972-73

About the Investigation

It began with a bungled break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s office at Washington’s Watergate complex. And it ended with the resignation of the most powerful man in the world, thanks in no small measure to the dogged reporting of The Washington Post. Today, Watergate is a symbol of investigative reporting worldwide, and the suffix “-gate” is used to describe scandals everywhere.

In 1972, following the Watergate break-in, the now famous reporting duo of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, with help from others on the Post staff, started to connect the dots between and the Watergate burglars. Their stories got little traction at first, as the White House stonewalled and Nixon won a landslide re-election that year.

But the evidence kept piling up. The team’s reporting helped unravel the threads of a massive criminal conspiracy, filled with break-ins, political dirty tricks, laundered money, illegal spying, and obstruction of justice. “Nixon had turned his White House, to a remarkable extent, into a criminal enterprise,” Bernstein and Woodward later wrote.

The journalists used a combination of public records, leaks, inside sources, and good old-fashioned shoe-leather reporting. They were helped by parallel investigations being run by a federal judge, the FBI, and the U.S. Congress. And, of course, there was Woodward’s super-secret source, code-named “Deep Throat,” who years later, following his death, would be revealed as Mark Felt, a top FBI official during the scandal.

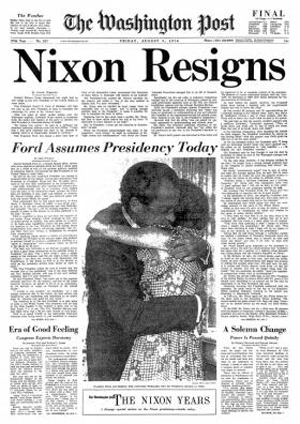

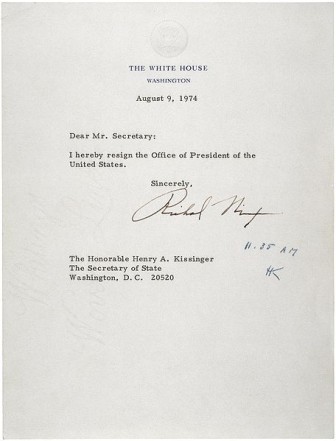

The team continued their reporting after Nixon’s reelection, until the scandal became a national sensation. Two years after the burglary, Richard Nixon became the first and only American president to resign. For their heroic reporting, Bernstein, Woodward, and The Washington Post received the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1973.

Impact

The impact of the Watergate scandal was extraordinarily broad. Following an impeachment trial, President Nixon was forced to leave office, becoming the first American president to resign. But Nixon was hardly the only casualty. The case resulted in criminal charges against 69 people, with convictions against 48 of them.

The impact of the Watergate scandal was extraordinarily broad. Following an impeachment trial, President Nixon was forced to leave office, becoming the first American president to resign. But Nixon was hardly the only casualty. The case resulted in criminal charges against 69 people, with convictions against 48 of them.

Following Watergate came a series of “good government” reforms, including tighter regulation of campaign activities, political contributions and lobbying, a stronger federal ethics law, and creation of a permanent independent special prosecutor to investigate wrongdoing by top officials. Periodic campaign finance reporters were required, public financing of presidential campaigns was introduced, and financial disclosure requirements were instituted for high-ranking officials in all three branches of the federal government.

The reforms also brought in a substantially strengthened federal Freedom of Information Act in 1974, and two years later the Government in the Sunshine Act mandated federal agencies to hold open-door meetings. The scandal also had a dramatic influence on journalism, sparking interest in investigative reporting by thousands of journalists and students, and setting an example for generations of reporters to come.